AFROPOLIS, PAGE 3

Kinshasa's relentless population growth gave rise to a new concentration of entertainment establishments in an area called Matonge, close to the center of the city's well-stretched boundaries. There a beer salesman named Raymond Franck opened the Vis-à-Vis nightclub, the district's showplace. Franco built his Un-Deux-Trois club in Matonge, and Tabu Ley followed with a club he called the Type K. Dozens upon dozens of other bars dotted the area along with record kiosks and food stands and other businesses that catered to the flourishing night life. And dozens upon dozens of bands sprang up to help sate the people's thirst for music.

Despite the fun that could be had, Kinshasa failed to fulfill its promise of jobs, at least in quantities sufficient to keep up with the exploding population. As a result, a degree of alienation had set in among the city's unemployed youth, even before independence. Many of them called themselves "Bills" after the heroes of American cowboy movies. They talked in a kind of slang called Hindoubill, named in part for the Hindu of Indian movies that were also popular at the time. Post-independence counterparts to the Bills were the somewhat more prosperous Yé-yés, named for the "yeah, yeah" cries of rock and roll. The Yé-yés had their own style and slang, which together with Hindoubill infused and invigorated the music and helped give birth to a new youthful generation of musical groups.

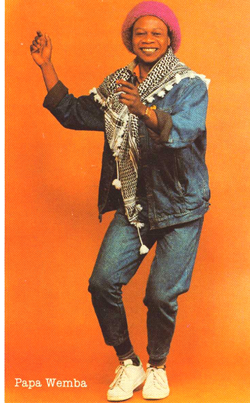

The first such band to gain widespread notoriety, Zaiko Langa Langa, made its debut in 1970. Zaiko's frequent personnel changes spawned a number of offspring, the remnants of which carry on to this day. The youth movement also inspired a craze for high fashion clothing called la sape. Musicians and their fans who indulged in this very expensive competition came to be known as sapeurs. Zaiko alumnus and leading sapeur, Papa Wemba, said what most who participated must have been thinking: "I had to set myself apart from the others. I had to have a look."8 The first such band to gain widespread notoriety, Zaiko Langa Langa, made its debut in 1970. Zaiko's frequent personnel changes spawned a number of offspring, the remnants of which carry on to this day. The youth movement also inspired a craze for high fashion clothing called la sape. Musicians and their fans who indulged in this very expensive competition came to be known as sapeurs. Zaiko alumnus and leading sapeur, Papa Wemba, said what most who participated must have been thinking: "I had to set myself apart from the others. I had to have a look."8

Life in the city imposed its frustrations as the Bills and Yé-yés could attest, but anyone who experienced the Kinshasa of the early seventies couldn't help feeling the city's overall sense of optimism and perhaps could understand why it would require a heroic effort for anyone to pull up stakes and return to the countryside.

President Mobutu's own optimism seemed to correspond with his consolidation of control and the concentration of cash in his bank accounts. His vision for himself and his country was expansive. Late in 1971 he announced that the name of the country would be changed to Zaire. Early the next year he decreed that all who carried a European-sounding name must shed it in favor of one authentically African (he became Mobutu Sese Seko). This was necessary, Mobutu would later explain, to give the Zairean "back his human dignity which colonization had completely destroyed by imposing assimilation and alienation. The dazzling development of Zairean arts since that time may be considered a renaissance, and proves the wisdom of our program."9

The principal Zairean art Mobutu surely had in mind was his country's sensational music. Its artists changed their names and rushed to promote the new authenticité. Franco recorded with old-timer Camille Feruzi, an accordionist popular in the 1940s. Others dropped their electric guitars in favor of the heretofore passé acoustic models, at least until the novelty wore off. Nearly everyone — save for the Catholic Church which tried mightily to defend "Christian" names — seemed to think that the exercise was one of Mobutu's better ideas.

Perhaps buoyed by the success of authenticity, Mobutu began to overreach. There had already been signs that the foundations of Zairean progress were less solid than they appeared. Mobutu's next move ensured that they would crumble. Toward the end of 1973 he announced that he would deliver Zaire from foreign control by turning all commercial establishments over to "sons of the country." Although he promised just compensation for the foreign business owners, the transaction was largely one of confiscation. Franco was awarded control of the Fonior record pressing factory, but most who took over the foreign firms were ill-equipped to manage them.

By the time the boxing match party invitations went out in 1974, it was clear that Zaireanization, as it was called, had turned into a disaster. Many businesses simply closed, their inventories sold and the proceeds pocketed by the new owners. Foreign exchange to finance imports of raw materials dried up. Franco's record pressing factory ran at reduced capacity, often resorting to the collection of old records to be melted down for pressing into new ones. Musicians could still make money in the clubs, but their record earnings evaporated.

Mobutu scrambled to undo the damage, but it was too late to recover. The experience of Loningisa proprietor Basile Papadimitriou was, perhaps, typical. "In 1976, a new order gave us the right to return to Kinshasa to pick up our business again, the president not being happy with the result of the Zaireanization of business," he recalled. "I returned and proceeded to inventory the goods turned over, the result of which was not good."10 Papadimitriou and most other foreign businessmen decided not to stay in Zaire.

Oblivious to the unfolding disaster, festival planners forged ahead. The spectacle of Zaire '74 with its astonishing array of musicians and the Ali-Foreman fight a month later (Ali won) introduced Kinshasa to the world. But it was a city whose glory days were dwindling. Television viewers couldn't see that the musicians were playing to a largely empty stadium. Most Zaireans couldn't afford the price of a ticket. Over the next few years the city's best musicians would move on to the more promising capitals of Paris and Brussels where Congolese music enjoyed a brief renaissance. Back home the party would wind down for a few more years, but Matonge would soon be just another remnant of an urban carcass. Kinshasa's golden era was coming to an end.

Endnotes

1. Raymond "Ray Braynck" Kalonji, interview with the author, Washington, D.C., September 1, 1994

2. Nikiforos Cavvadias, interview with the author, Brussels, January 3, 1997

3. Manu Dibango, interview with the author, Paris, August 24, 1991

4. Edo Ganga, interview with the author, Brazzaville, June 7, 1993

5. Colin M. Turnbull 1962, The Lonely African, New York, p. 125

6. Sam Mangwana, interview with the author, Silver Spring, Maryland, October 15, 1990

7. Dibango, 1991

8. Papa Wemba, interview with the author, Paris, August 30, 1991

9. Jean-Louis Remilleux 1989, Mobutu: Dignity for Africa, Paris, p. 107

10. Basile Papadimitriou, letter to the author, November 10, 1993 |