This is the English version of the essay written for the catalog of the Afropolis exhibition held at the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum in Cologne. For more information click HERE to go to the exhibition web site. An English edition of the beautiful, 300 page Afropolis catalog---Cairo, Lagos, Nairobi, Kinshasa, Johannesburg-- has just been published (April 2013). To order a copy visit Jacana Press.

KINSHASA: CONGO MUSIC

Copyright © 2010 by Gary Stewart

A party invitation issued from central Africa in 1974. The time: late September. The place: Zaire — the old Belgian Congo renamed by its autocratic president, Mobutu Sese Seko. Many of the preeminent entertainers of the latter half of the twentieth century — James Brown, Celia Cruz, Miriam Makeba, and more, along with homegrown stars like Franco, Abeti, and Tabu Ley Rochereau — would come to the capital, Kinshasa, to perform in a three-day extravaganza prior to a heavyweight title fight between champion George Foreman and challenger Muhammad Ali. The music on the stage and the mayhem in the ring would show the world: Zaire aimed for greatness. That this was the summit, that from this point Zaire would fall more rapidly, and perhaps more disastrously than it had risen, would not be known for a few more years. In 1974 it was time to recognize what appeared to be the country's tremendous progress, the most enduring elements of which, it turned out, came from the realm of the arts. And what better way to celebrate than to showcase the nation's stellar musicians alongside their famous counterparts from abroad. After all, Zaire's musicians already dominated the popular music scene in Africa. Two of its biggest stars, Tabu Ley and Abeti, had even played the renowned Olympia concert hall in Paris. The rest of the world should know about this Zairean treasure.

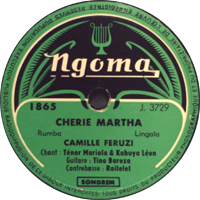

The music that Ley and Abeti and their immensely popular peers had raised to a level of virtuosity that rivaled their international colleagues came to be called Congolese rumba or simply Congo music: strains of the Cuban son repatriated on radios and records and re-Africanized with a pinch of jazz and a dash of cabaret. This new music, which was sung in Lingala and played primarily on guitars, transcended barriers of ethnicity and culture and helped to bind disparate peoples together. The Congolese rumba was a product of Kinshasa's urban milieu, but the city itself, in no small measure, was a product of the music too. The music that Ley and Abeti and their immensely popular peers had raised to a level of virtuosity that rivaled their international colleagues came to be called Congolese rumba or simply Congo music: strains of the Cuban son repatriated on radios and records and re-Africanized with a pinch of jazz and a dash of cabaret. This new music, which was sung in Lingala and played primarily on guitars, transcended barriers of ethnicity and culture and helped to bind disparate peoples together. The Congolese rumba was a product of Kinshasa's urban milieu, but the city itself, in no small measure, was a product of the music too.

The musical accomplishments that reached full flower in Mobutu's Congo-Zaire could be traced to a process of urbanization unintentionally set off during the notorious, nineteenth century rule of Belgium's King Leopold II. Forced labor in the countryside — the collection of wild rubber and ivory to support the king's lavish spending at home — irreparably disrupted rural life. The transfer of the king's personal African plantation to control of the Belgian government in 1908 abated the worst of the Congo's outrages, but life could never return to the way it had been before the coming of the white man. Two world wars demanded more from rural Africans who were required to cultivate the land and mine its precious minerals to help supply the armies of Europe. Some were recruited to join the fighting, others to work the factories in new cities that sprang up near river banks and rail heads.

The Belgian government recruited its own citizens to bring their skills and entrepreneurial spirit to the colony. Other Europeans — whether seeking refuge from the Great Depression or simply thirsting for adventure — came to the Congo for a fresh start. Most of these newcomers gravitated to the burgeoning cities where they started businesses, worked in factories, or staffed the colonial bureaucracy.

For both Africans and Europeans the biggest attraction was Léopoldville, today's Kinshasa, a town on the banks of a wide place in the Congo River some 240 miles upstream from the Atlantic. Quite rapidly the town became a city, more so after it was made the colony's capital in 1930. Colonial authorities tried mightily to limit its growth, but the numbers of people abandoning rural life and its hardships swamped their efforts.

Nearly all the musicians who would go on to win the hearts of the entire continent emigrated to Léopoldville or were born to parents who had already made the journey from the countryside. Franco, the guitarist who led the legendary O.K. Jazz for more than thirty years, came from Sona Bata, south of Léo, as a boy in the 1940s. Dr. Nico, a leader in seminal groups African Jazz and African Fiesta, moved with his parents from Kasai Province to the east. Tabu Ley's family had come to town from Bagata along the Kwilu River to the north. As a young girl Abeti fled to Léopoldville with her mother in the wake of violence in Stanleyville (Kisangani) during the unrest that attended Congolese independence. Singer Sam Mangwana's parents had escaped an authoritarian Portuguese regime in Angola to start over under the somewhat less repressive Belgians. Several musicians, like clarinetist Jean Serge Essous and singer Edo Ganga who would work in O.K. Jazz, crossed the river from Brazzaville in the French Congo. Similar stories could have been told by a million others.

Europeans contributed to Léopoldville's fertile mix, although in the evenings they kept themselves separate. "After nine o'clock you are not allowed to be in the white part of town," musician Ray Braynck recalled. "They blew a bugle horn for you to get out of there."1 (The curfew failed to deter Braynck, he said, as he and a friend would sometimes remain, hiding until after midnight, so they could steal coconuts.) During the day the white area opened to all, for there much of the colony's business transpired. The white-owned shops needed African customers in order to prosper. Along with necessities like food and clothing, some merchants stocked cheap guitars, foreign records and the machines to play them, and radios that could secure a link to the outside world.

Among Léopoldville's entrepreneurs, one of the earliest to recognize that a certain synergy might develop between music and commerce was a Belgian ex-army sergeant named Jean Hourdebise. He established a radio station called Congolia in 1939 and supplemented its coverage by erecting a series of loudspeakers in African quarters of the city to reach the many who could not afford radios. To attract African listeners he began to record African musicians and then play their works on the air. The number of listeners increased following this innovation, and that attracted merchants who were willing to pay to have their firms mentioned on Congolia's programs. One of the first to sing on the radio was a boatman named Antoine Wendo Kolosoyi, who would parlay the opportunity into a successful career that continued for more than sixty years.

|