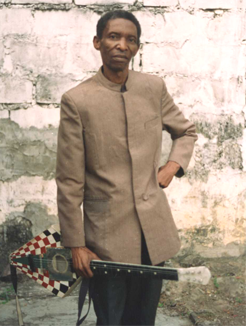

Mwamba Dechaud Mwamba Dechaud

1939 - 1999

Kinshasa continues to be the source of grim news. Mwamba Mongala "Dechaud," "the guitarist who made Lucifer and his 10,000 devils dance," died during the night of September 4-5, 1999. In clinical terms his illness was brief; death dispensed by the ambiguous natural causes. But the poverty and neglect that demeaned Dechaud's last years was more man-made than natural. And it almost certainly contributed to his demise. Yet Dechaud was a hearty soul whose 64 years spanned the entire history of modern Congolese rumba. In spite of the dire circumstances he endured, Dechaud out-lived his contemporaries, including his younger brother, the virtuoso guitarist Docteur Nico.

Dechaud was born Charles Mwamba in Luluabourg, Belgian Congo, in 1934 or 1935. He and his family joined in the rural exodus following World War II by moving to the colonial capital Léopoldville (today's Kinshasa). There Dechaud rose to musical prominence as a teenager in 1950 singing with the era's most popular entertainer, Zacharie Elenga, better known as "Jhimmy." Jhimmy strung his guitar with two E strings, the second in place of the normal D string. That style came to be known as the mi-composé, and Dechaud picked it up as he learned to play the guitar at Jhimmy's side.

By the mid-fifties, as a member of the seminal group African Jazz, Dechaud began to define what it meant to be an accompagnateur or rhythm guitarist. Congo-Brazzaville author Sylvain Bemba once wrote that Dechaud's style was "original, made of pseudo hesitations, anticipations, and obvious deliberation all coming together in the most beautiful rhythmic working. No guitarist has ever known better than Dechaud how to eroticize the rumba."

In African Jazz, and later in African Fiesta and African Fiesta Sukisa, Dechaud teamed with his brother Docteur Nico to form Congolese music's most formidable guitar duo. Dechaud fashioned a rhythmic framework for his brother to embellish, and in the process he set the standard for Congolese rhythm guitar. Those who followed, Lokassa ya Mbongo, Bopol Mansiamina, and dozens of others owe an incalculable debt to the stylings of Mwamba Dechaud.

After African Fiesta Sukisa disbanded around 1973, and in the face of his brother's accompanying decline, Dechaud faded into a state of involuntary retirement. He joined in Nico's short-lived comeback in the early eighties, then slipped again from view when Nico died in 1985.

Dechaud's most famous work, "African Jazz Mokili Mobimba" (often shortened to "Africa Mokili Mobimba"), should have provided him with a comfortable living in spite of the inactivity of his later years. The original version, recorded with African Jazz, and subsequent covers by other artists have been among Congolese music's most consistent sellers over the years. But, as often happens in the nefarious world of the Congolese music business, little remuneration reaches a work's creator. And indeed little reached Dechaud. It has been said that Dechaud's boss in African Jazz, Joseph Kabasele, bought the rights to his employees' compositions. If so, royalties, had they been paid, would have gone to Kabasele and his estate. Other artists who covered the song often confused the situation further by crediting the song to Kabasele or re-naming it and crediting themselves.

As a result, Dechaud lived much of the end of his life nearly destitute, without so much as a guitar of his own to play. He performed occasionally with borrowed equipment in a band of old-timers called Afric'Ambiance. For the most part, however, Dechaud passed the time in a modest two-room bungalow provided by Nico's children, receiving an occasional visitor but otherwise keeping much to himself.

In December of 1993, thanks to the Voice of America's Leo Sarkisian, the U.S. Embassy in Kinshasa honored Dechaud for his contribution to Congolese (Zaïrean) music. The American chargé d'affaires presented the instrument-less musician with a new acoustic guitar at a grand ceremony attended by a large number of fans, friends, and dignitaries—all of whose lives had been brightened by his music. Little was heard about Dechaud after that, until the announcement in September of his death. Perhaps the man, who in life made Lucifer and his 10,000 devils dance, now does the same for St. Peter and the angels.

© 2000 Gary Stewart

This article first appeared in The Beat, vol. 19 no. 1, 2000. |