POLITICAL HISTORY, PAGE 3

Taking heart from Livingstone's explorational success, others joined the effort to map new territory. Two Englishmen, Richard Burton and John Speke, made it from Zanzibar to Ujiji on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika in 1858. Two years later Speke and James Grant set out again from Zanzibar on a journey that would take them to Lake Victoria and on up the Nile to the Mediterranean. But for the makers of Congo music and their ancestors, the most important explorer was one John Rowlands, soon to become famous as Henry Morton Stanley. Taking heart from Livingstone's explorational success, others joined the effort to map new territory. Two Englishmen, Richard Burton and John Speke, made it from Zanzibar to Ujiji on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika in 1858. Two years later Speke and James Grant set out again from Zanzibar on a journey that would take them to Lake Victoria and on up the Nile to the Mediterranean. But for the makers of Congo music and their ancestors, the most important explorer was one John Rowlands, soon to become famous as Henry Morton Stanley.

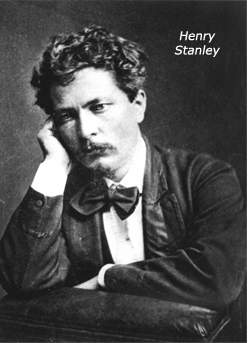

In 1841, the same year Dr. Livingstone took up his first African posting, Stanley was born to the unwed Elizabeth Parry in the north of Wales. Named for his reputed father, John Rowlands, and abandoned by his mother, he spent the next sixteen years being shunted among unwelcoming relatives and the St. Asaph Union Workhouse, a prison-like home for delinquents, orphans, and assorted misfits. At age eighteen, a chance encounter on the wharves of Liverpool put Rowlands on board a ship bound for New Orleans. There he found the first real family he had known in the person of English businessman Henry Hope Stanley from whom the young Rowlands took a new name.

For the new Henry Stanley—after some experimentation he would add the name Morton—this period of affection and tranquility was short-lived. The erupting civil war in the United States cast him into a bizarre odyssey that included service in the Confederate army, the Union army, the merchant marine, and the U.S. Navy—each of which he deserted—and finally to a career as a journalist. He reported briefly for the Missouri Democrat covering the westward push of the American frontier and the "Indian problem." But it was as an employee of the disreputable New York Herald that Africa would come to know of Henry Stanley.

In 1868, as Livingstone trudged along in search of the origins of the Nile and the Congo, Stanley first set foot in Africa to cover the British raid in Abyssinia. Three years later, on assignment from the Herald, he mounted his first expedition, a caravan of two hundred men and six tons of supplies (including an enamel bath and Persian carpet), to tramp off in search of the famous Dr. Livingstone, whom no white man had seen since he disappeared into the bush on his latest journey in 1866 and whose fate was the subject of much speculation and rumor. Their historic meeting at Ujiji on the shores of Lake Tanganyika was a passing of the baton. Old and tired, Livingstone would march stubbornly on to his death a few months later. Young and exhilarated by their encounter, Stanley would live to explore again. He would chart the uncharted center of Africa that had so completely mesmerized the old doctor.

In November of 1874, Stanley set out once again from Zanzibar, this time under joint sponsorship from the New York Herald and London's Daily Telegraph. He had been frantic to get under way. Another explorer, British Lieutenant Verney Cameron, had had more than an eighteen-month head start. He could steal Stanley's thunder.

The cast assembled to search for Livingstone, spectacular though it had been, paled in comparison to Stanley's newly recruited entourage, some 350 strong carrying more than eight tons of supplies, including the sections of a forty-foot boat. Stanley, supported by three white companions and a half-mile-long caravan of warriors, porters, and servants, aimed to circumnavigate three of the Great Lakes, Victoria, Albert, and Tanganyika, then push on to the Lualaba River, Livingstone's furthest westward penetration. Then he would go the late doctor one better. He would follow the mysterious river to where he believed it would join the Congo and cross Africa to the Atlantic Ocean. It was to be Stanley's master stroke, a journey of such epic proportions that even his most strident critics would have to recognize his achievement. Never mind the consequences for Africa.

Farther and farther from the comforts of the coast, the expedition met increasing hostility. Under threat of a British blockade, the sultan of Zanzibar had banned the island's slave markets thereby pushing the trade in human beings deeper into the mainland interior. For all the Africans knew, Stanley's caravan was nothing more than another party of slave raiders from whom they needed to protect themselves. And Stanley, unlike his hero Livingstone, whose peaceful, principled behavior among Africans was widely recognized, was not above relishing a good fight. Both men had shared an abhorrence of the slave trade and fervently hoped that one day white missionaries could uplift the "savages," but their methods differed sharply. Livingstone had once written, "It is hoped that we may never have occasion to use our arms for protection from the natives, but the best security from attack consists in upright conduct."20 Stanley too would negotiate passage through territory and barter for food where he could, much of the eight tons of supplies contained cloth, beads, and other items expressly for that purpose. But when met with resistance, he would attack the local people and plunder their villages. His was often a bloody quest.

Two of the three lakes, Victoria and Tanganyika, submitted to Stanley's will. He never reached Lake Albert, forced instead to retreat in the face of overwhelming hostility from the surrounding people. Back at Ujiji in May 1876, where five years earlier he had met Livingstone, Stanley and his followers rested and regrouped. The entourage had been decimated. Many of those who hadn't died from sickness or battle wounds had deserted. Maintaining discipline and loyalty was a constant challenge. Stanley resorted to placing miscreants in slave restraints, iron collars around necks, wrists, and ankles, connected by heavy chains. A week's march in this condition proved more remedial than flogging. It was a tactic Stanley undoubtedly picked up from his encounters with Arab slavers in the bush. All too often he had seen the pathetic columns of starving, manacled men, women, and children stumbling hopelessly onward to the Ujiji slave markets.

Rest and new recruits at Ujiji bolstered the expedition, but most encouraging of all for Stanley, he learned from the Arabs that his rival, Cameron, had turned south toward Angola upon reaching the Lualaba. The river's northern reaches and possible outlet to the Atlantic were Stanley's alone for the taking. In September of 1876 his refurbished caravan sailed across Lake Tanganyika to begin the march to the Lualaba. A month later they reached its banks. A few days after that, in the town of Kasongo, they met the infamous Tippu Tib.

His real name was Hamed bin Muhammed. Ivory and slaves were his money, and he was ruthless in their pursuit. Stanley enlisted him in the exploration of the Lualaba. In return for five thousand dollars Tippu Tib agreed to escort the expedition sixty days north along the river beyond Nyangwe, Livingstone and Cameron's farthest venture. After that Stanley felt he could keep his people together. Potential deserters would surely think twice for they were in territory where they knew no local language, and retreat towards Nyangwe would mean confrontation with Tippu Tib's men and certain capture or death.

|