Pamelo Mounk'a Pamelo Mounk'a

1945 - 1996

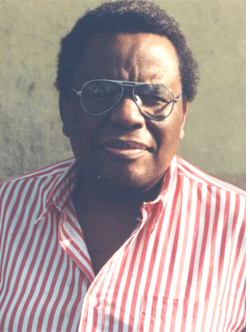

I met him in 1993, a large man with a powerful voice and an appetite for life. Pamelo Mounk'a rose from his chair and willed himself unsteadily to the door. The sun was setting on Brazzaville, and I wanted to get some photos before we lost the light. I could see his feet, swollen and disfigured, the effects of diabetes he said. It had taken both his parents. I guess he knew that it would claim him too, but on that day, with his vital and bountiful intellect at full vigor, death was difficult to perceive.

In the space of thirty years, Mounk'a's exceptional voice and appealing songs had earned him the career of his dreams. And the boyish good looks didn't hurt either.

"Did you ask him how many children he has?" his friend Jean-Serge Essous wanted to know.

"No."

"Well, you didn't do half your job then," he said.

"How many does he have?"

"Twenty-seven. And those are just the ones we know about. He started making them in high school. He's been engaged eleven times that I know of."

"Has he ever married?" I asked.

"Never. A handsome young man in front of the mic, 600 or 1000 people in the audience, half of them women. It was easy for him. At times you'd go to his house and you'd think you were in the pediatric ward of a hospital."

Pamelo Mounk'a fathered his famous songs as easily as he did his children. The first, he said, came to him in a dream around the age of nine. He was Yvon Mbemba then, a schoolboy in Brazzaville, capital of the French Congo, where he had been born in 1945. He often crossed the Congo River to Léopoldville (Kinshasa) in the Belgian Congo to visit relatives. There he hung around the Kongo Bar to listen to the era's two great bands, African Jazz and O.K. Jazz, and maybe get a glimpse of stars like Franco and Joseph Kabasele.

Pamelo had an ear for languages, especially Spanish, which he favored for his compositions. Like its musical counterpart, the rumba, it fit Congolese song rather well. He called himself Pablito and began to think he could be a musician. Around 1961, shortly after the two Congos gained their independence, he met his idol, Tabu Ley Rochereau. Rochereau liked the kid's voice and his songs and took him under his wing to coach him in the fine points of performing.

By 1963, it looked like Pablito might get to sing with African Jazz, but a rebellion was in the works. Rochereau and the rest of the band quit Kabasele's employ. Lacking a passport, Pablito was left behind when the musicians flew off to Brussels to record their first songs as African Fiesta. He returned to Brazzaville where Essous drafted him into the era's other great band, Orchestre Bantou. At the audition, Pamelo recalled, he didn't even know their music.

His first tour with Orchestre Bantou lasted for only a year. He felt, he said, that he was expected to carry too much of the vocal load before he was really ready. He needed a period of apprenticeship, so when Rochereau sent an emissary to lure him back to African Fiesta, Pablito went.

Towards the end of 1964, with relations between the two Congos at a low point, Congo-Léopoldville's prime minister, Moise Tshombe, expelled all citizens of Congo-Brazzaville. Pablito, now a more seasoned singer, returned home to Orchestre Bantou. During this period he adopted the name Pamelo when informed by SACEM, the French authors' rights society, that they already had artists named Pablito and Mbemba registered. A year later, another young singer, Côme Moutouari, better known as Kosmos, joined the band. Paired together for the next seven years, Pamelo and Kosmos brought Orchestre Bantou its greatest success. With songs like "Masuwa" (the ship) and "Amen Maria" Pamelo won the hearts of music lovers on both banks of the Congo River.

Dissension in the ranks in 1972, caused a three-way split in the band, known by then as Les Bantous de la Capitale. Pamelo, Kosmos, and another singer, Célestin Kouka, formed one faction they called the Trio CEPAKOS and recruited new musicians, Orchestre Le Peuple, to back them. A second faction led by singer Edo Ganga called itself Les Nzoi (the bees), while the original Bantous de la Capitale of Essous and Nino Malapet carried on with new recruits.

Pamelo earned international acclaim as a solo artist in the early eighties. Seeing the success that other Congolese and Zaïrean artists like Sam Mangwana and Théo Blaise Kounkou were having in Paris, Pamelo decided to follow them to the French capital. There he met Eddy Gustave, a musician and producer from Guadeloupe. Gustave agreed to produce an album, but he urged Pamelo to adopt a second name. After mulling it over for a couple of days he came up with Mounk'a. It means "glory" in the language of the Bateke, he said.

Pamelo Mounk'a's first release on Gustave's Eddy Son label exceeded even his inflated expectations. On the strength of its title track, "L'Argent Appelle L'Argent" (money attracts money), the album rang up sales across Africa and Europe and helped African music gain a foothold in the insular U.S. market. The follow-up, Samantha—with its great songs and slick, green fold-out cover that proclaimed Pamelo "No. 1"—sold equally well. By their fourth collaboration, however, Pamelo and Gustave fell out in a dispute over royalty payments.

Pamelo rejoined Les Bantous de la Capitale, as chef d'orchestre this time, but his health began to deteriorate as the eighties wound to a close. He relinquished control of the band to try to recover his health, a goal that eluded him for the rest of his life. Pamelo took one last fling at performing in the early nineties with a disgruntled faction of Les Bantous called Bantous Monument. For the most part, however, his declining health kept him off the stage and out of the studio. Trips to Paris for treatment brought periods of relief but never recovery. Friends say he didn't follow the doctors' regimen. Pamelo said he feared they would amputate his feet. Someone put a curse on him, he said in 1993. He preferred to obtain treatment from a local herbalist.

The effects of his diabetes claimed Pamelo's life in a Brazzaville hospital on 14 January. According to his friend Essous, Pamelo's body was laid out at the Institute of Fine Arts in Brazzaville's Poto Poto section so friends and fans could pay their last respects. Musicians from around the country gathered at spontaneous vigils to play the old songs in memory of their friend and colleague. Simaro Lutumba of O.K. Jazz led a delegation from Zaïre to a final grande veillée on Friday the 19th. Burial in Brazzaville took place the following day.

Like the legends of Congolese/Zaïrean music who passed before him, Pamelo Mounk'a leaves a legacy of incredible breadth. From his work for Tabu Ley, through the glory years with Les Bantous de la Capitale, to his astonishing achievements as a solo artist, Pamelo Mounk'a earned well his accolades. For many of his fans the words to "Masuwa" must now seem a bit more personal.

The boat has left,

Taking you to another country.

Above all don't forget you left me on the bank,

I wait for you.

The boat is now far away,

I have tears in my eyes, Pamelo.

© 1996 Gary Stewart

This article first appeared in The Beat, vol. 15 no. 2, 1996. |