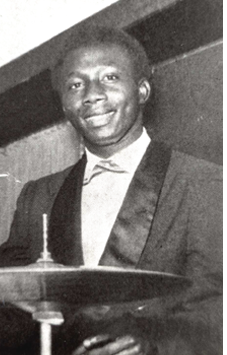

Roger Izeidi Roger Izeidi

1935 - 2001

One of the last surviving members of the fabled African Jazz, Roger Izeidi, died in Kinshasa during the third week in January. He was 65 years old. Izeidi's health had been deteriorating in recent years. He spent the first several months of 2000 in Brussels undergoing medical treatment for an unspecified illness. Friends in the Belgian capital noted that the ordinarily vigorous Izeidi was hampered by failing eyesight and hesitant speech. Doctors, it seems, could do little to alleviate his condition.

Roger Dominique Izeidi was born in Kinshasa, then known as Leopoldville, on Nov. 20, 1935. His passion for music developed in school and church where he sang in various choruses. In 1953, he was the first musician to sign with the Compagnie d'Enregistrements Folkloriques Africains (CEFA), a newly opened recording studio run by Belgian jazz guitarist Bill Alexandre. Izeidi wrote songs, sang, and played maracas. He also recruited talent for the studio, most notably Victor "Vicky" Longomba who would go on to fame with O.K. Jazz.

Izeidi's friendship with Joseph Kabasele of the rival Opika studio hastened the formation of African Jazz. Where CEFA musicians were allowed, even encouraged, to take their studio-owned instruments home, Opika's were not. So, Kabasele and several of his studio mates played Kinshasa's bars with Izeidi and other CEFA musicians on CEFA instruments. African Jazz, led by Kabasele and including Izeidi, emerged from this mix.

The immensely popular African Jazz became the prototype of the modern Congolese rumba band. Izeidi contributed songs to the band's repertoire and sang behind Kabasele. In addition he helped to popularize the use of maracas, adding their distinctive slosh to Congolese music's developing rhythm section that included conga drums and acoustic upright bass. Izeidi traveled to Brussels in 1960 as part of the temporarily re-vamped African Jazz that would entertain delegates to the round table conference on independence for the Belgian Congo. The band recorded several songs in Brussels, including the incomparable "Indépendance Cha Cha."

As a complement to his musical endeavors, Izeidi learned the business side of making records from CEFA's Bill Alexandre. When the Belgian company Fonior purchased CEFA in 1955 and began construction of a new pressing plant in Kinshasa, Izeidi remained with the company in a business capacity while performing with African Jazz. After independence, Izeidi bought CEFA, albeit without the label's valuable back catalog, and used it as a foundation for his business ventures. Several bands, including O.K. Jazz and Bantous de la Capitale, traveled to Brussels under Izeidi's auspices to record at Fonior. Their works were then issued back home on Izeidi's CEFA label. A second Izeidi label, Tcheza (dance, in Swahili), issued works by a number of newer bands including Paul "Dewayon" Ebengo's Cobantou, Johnny Bokelo's Conga Succès, and Léon "Bholen" Bombolo's Négro Succès. Izeidi was a founding member of ONDA, the national office of authors's rights and served a term as vice-president of ONDA's successor, SONECA.

In 1963, Izeidi, guitarist Docteur Nico Kasanda, and singer Tabu Ley Rochereau, led a revolt that saw all the members of African Jazz leave Kabasele to form the new band African Fiesta. Through his business connections with Fonior, Izeidi secured recording dates for the band in Brussels and created the new Vita label to issue its works at home. When African Fiesta split at the end of 1965, Izeidi and Rochereau led the faction that became African Fiesta National, while Nico formed African Fiesta Sukisa. Four years later Rochereau forced Izeidi out, effectively ending the maracas player's performing career.

Izeidi devoted the rest of his life to his business interests in the increasingly inhospitable economic climate of the Congo. When the country's President Mobutu changed its name to Zaïre in October of 1971 and launched his authenticity campaign, Izeidi dropped his Western names and became Izeidi Mokoy. He gradually withdrew from pop music altogether, concentrating instead on recording traditional music for his Paka Siye label.

Throughout the eighties and nineties, Izeidi worked to restore Congolese music's vast catalog to its authors. Fonior's archive of Congolese master tapes had been sold to the French company Sonodisc as part of the bankruptcy proceedings that followed Fonior's collapse in 1980. Until his death, Izeidi maintained that the tapes were not Fonior's property, and, in any case, the author's rights belonged to the authors, not the record companies involved. His appeals to Zaïrean government ministers to intervene on behalf of the musicians went unheeded. Letters to the European parties concerned lacked the authority a legal proceeding, which he could not afford to initiate, would have carried.

With Izeidi's passing, only Tabu Ley remains from the first ranks of the illustrious African Jazz. Le roi des maracas (the king of maracas) leaves a brother, the noted guitarist Faugus Izeidi, a wife and several children. He was buried on Jan. 25, 2001, in Kinshasa.

© 2001 Gary Stewart

This article first appeared in The Beat, vol. 20 no. 2, 2001.

|