|

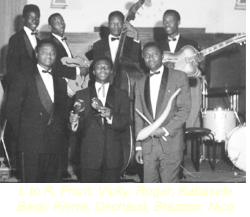

African Jazz, seminal Congolese rumba band, formed 1953-55; disbanded 1969. Notable early members: Tino Baroza (born Congo-Kinshasa, 1930; died Yaounde, Cameroon, Dec. 2, 1968; guitar), Etienne "Baskis" Diluvila (born Kinshasa, 1932; percussion., vocal), Roger Izeidi (born Kinshasa, Nov. 20, 1935; died Kinshasa, Jan. 2001; maracas, vocal), Joseph Kabasele (born Matadi, Congo-Kinshasa, Dec. 16, 1930; died Kinshasa, Feb. 11, 1983; vocal), Docteur Nico Kasanda (born Mikalayi, Congo-Kinshasa, July 7, 1939; died Brussels, Sept. 22, 1985; guitar), Antoine "Depuissant" Kaya (born Kinshasa, 1934; drums), Dominique "Willy" Kuntima (born Kinshasa, July 31, 1931; died Kinshasa, Jan. 25, 1972; trumpet), Isaac Musekiwa (born Zimbabwe, 1930s; died Kinshasa, 1990; saxophone), Charles "Dechaud" Mwamba (born Kananga, Congo-Kinshasa, 1934 or 1935; died Kinshasa, Sept. 4, 1999; guitar), Albert Taumani (born Kinshasa, 1935; bass). African Jazz, seminal Congolese rumba band, formed 1953-55; disbanded 1969. Notable early members: Tino Baroza (born Congo-Kinshasa, 1930; died Yaounde, Cameroon, Dec. 2, 1968; guitar), Etienne "Baskis" Diluvila (born Kinshasa, 1932; percussion., vocal), Roger Izeidi (born Kinshasa, Nov. 20, 1935; died Kinshasa, Jan. 2001; maracas, vocal), Joseph Kabasele (born Matadi, Congo-Kinshasa, Dec. 16, 1930; died Kinshasa, Feb. 11, 1983; vocal), Docteur Nico Kasanda (born Mikalayi, Congo-Kinshasa, July 7, 1939; died Brussels, Sept. 22, 1985; guitar), Antoine "Depuissant" Kaya (born Kinshasa, 1934; drums), Dominique "Willy" Kuntima (born Kinshasa, July 31, 1931; died Kinshasa, Jan. 25, 1972; trumpet), Isaac Musekiwa (born Zimbabwe, 1930s; died Kinshasa, 1990; saxophone), Charles "Dechaud" Mwamba (born Kananga, Congo-Kinshasa, 1934 or 1935; died Kinshasa, Sept. 4, 1999; guitar), Albert Taumani (born Kinshasa, 1935; bass).

African Jazz evolved from the collection of session players employed by Opika recording studio in colonial Léopoldville (Kinshasa). Opika, run by brothers Gabriel and Joseph Benetar, was one of several, mostly Greek-owned studios where musicians could earn a decent living making records in various groupings according to the needs of each session's leader. The players who would become African Jazz began to record together with such consistency that they decided to form a permanent band.

Popular singer Joseph Kabasele emerged as the group's leader, with the guitar-playing brothers Nicolas Kasanda (later "Docteur Nico") and Charles "Dechaud" Mwamba at the core of the instrumental section. Band played Latin-style songs and contributed heavily to the development of the Congolese rumba, essentially a variant of the Cuban son, which had begun to evolve in the late forties and early fifties. Early songs like "Trio Companeiro" and "Pause Adjes" used acoustic guitars, but by the mid-fifties African Jazz made the switch to electric guitars. Change occurred when Belgian jazz guitarist Bill Alexandre came to Léopoldville to open another recording studio. Alexandre brought his electric guitar, and within a short span nearly every guitarist in town went electric.

African Jazz moved to a new studio called Esengo when Opika closed in 1957. There they worked in tandem with another group called Rock'a Mambo, sometimes issuing collaborative works under the name African Rock. African Jazz revamped temporarily in 1960 when two members of rival O.K. Jazz, Antoine "Brazzos" Armando and Vicky Longomba, joined Kabasele, Nico, Dechaud, Izeidi, and drummer Pierre Yantula to entertain delegates to the round table conference on Congolese independence in Brussels. There, African Jazz recorded its most famous side, "Indépendance Cha Cha," a song that resounded across Africa as European colonialism collapsed.

Back home the band reverted to what was essentially its old lineup. Promising singer Pascal Tabou, known as "Rochereau" (later Tabu Ley), emerged as a force within the band at this time. Cameroonian sax player Manu Dibango joined in 1961. African Jazz continued to play concerts and record in spite of the political crisis gripping the country. Songs of the period included Kabasele's "Matata Masila na Congo," a plea for an end to the troubles, along with lighter fare like Rochereau's "Bonbon Sucré" (sweet candy) and Baroza's "Mayele Mabe" (evil mind). Band also recorded a classic to rival "Indépendance Cha Cha" in Dechaud's "African Jazz Mokili Mobimba" (African Jazz all over the world), perhaps the most covered song in Congolese music's repertoire.

Dissension within the band peaked in 1963 when all the musicians deserted Kabasele and formed African Fiesta (See African Fiesta Sukisa; Afrisa). Kabasele regrouped by joining forces with singer Jean Bombenga and his Vox Africa to form a new African Jazz. The new formation recorded and played concerts from time to time, but ultimately African Jazz could not survive the demise of its original lineup.

In its most productive period, late fifties and early sixties, African Jazz was one of the best and most important African bands of the twentieth century. It was the first significant band to emerge from the various pools of session musicians who populated Congo-Kinshasa's earliest recording studios, and it became the prototype for nearly all Congolese bands that followed. The group strongly influenced the development of the Congolese rumba and produced some of the era's greatest stars including Kabasele, Nico, and Rochereau. African Jazz helped spread Congolese music beyond the boundaries of central Africa and in the process influenced the evolution of popular music styles in both East and West Africa.

© 2011 Gary Stewart

SELECT DISCOGRAPHY

African Jazz (original): Merveilles du Passé (Sonodisc CD36503) sixties recordings reissued 1991; Grand Kalle & L'African Jazz vol. 1 (Sonodisc CD36579) sixties recordings reissued 1997; Grand Kalle & L'African Jazz vol. 2 (Sonodisc CD36582) sixties recordings reissued 1997.

African Jazz (new formation): Le Grand Kalle & L'African Jazz (Sonodisc CD36536) sixties recordings reissued 1993; Grand Kalle & L'African Jazz (Sonodisc CD36585) sixties recordings reissued 1997.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

M. Lonoh, Essai de commentaire sur la musique congolaise moderne, (Kinshasa, 1969); S. Bemba, 50 ans de musique du Congo-Zaire (Paris, 1984); C. Stapleton & C. May, African All-Stars (London, 1987); M. Dibango, Three Kilos of Coffee (Chicago, 1994); Manda Tchebwa, Terre de la chanson (Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 1996); G. Stewart, Rumba on the River (London and New York, 2000).

|